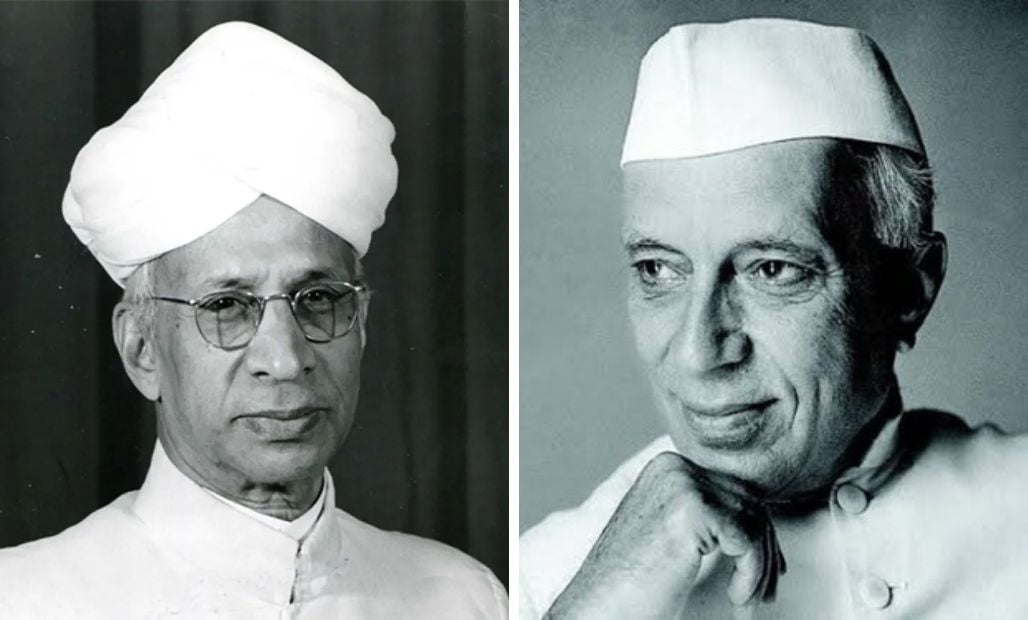

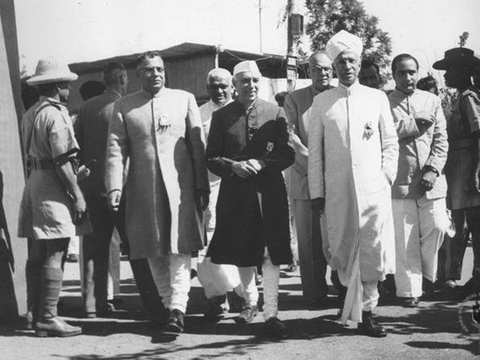

In the historic month of September 1946, a pivotal moment in India’s history unfolded when Pt Jawaharlal Nehru assumed a prominent role in the Interim Government. With great clarity and resolve, Nehru declared that India’s foreign policy would henceforth be characterized by independence and an unwavering commitment to its own national interests. Here’s an explainer on how Dr. S Radhakrishnan Assisted Nehru in Developing the Non-Aligned Policy.

Source: Veeti

On the occasion of Teachers’ Day, celebrated annually on September 5th to honor Dr. S Radhakrishnan’s birthday, we delve into a lesser-known aspect of India’s former President. Dr. Radhakrishnan, not only an eminent philosopher but also a statesman, played a pivotal role in shaping the non-alignment movement alongside Prime Minister Nehru.

His contributions to this diplomatic endeavor were significant, particularly during his tenure as India’s Ambassador to the Soviet Union in 1949, where he effectively conveyed this policy to diverse global audiences. This introduction sheds light on the multifaceted character of Dr. S Radhakrishnan.

When Prime Minister Nehru was creating the non-alignment policy, the world was in the midst of the Cold War. The United States was aggressively gathering nuclear weapons, and their diplomatic actions were very calculated. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union was wary of countries and leaders who didn’t support them and criticized non-alignment as working with British imperialism. This made it a challenging time for Nehru as he tried to navigate these different international dynamics.

As mentioned in Volume 2 of his biography, Pt. Nehru was resolute in his stance, as observed by his biographer S. Gopal. He had no intention of changing his policy. He was committed to creating a policy where India would make its own decisions on every issue, no matter the challenges it posed. He believed this was the morally right thing to do.

In early January 1947, Prime Minister Nehru wrote a letter to Ambassador KPS Menon, who was taking on the role at the embassy in China. In the letter, Nehru explained their general policy, which was to stay out of getting deeply involved in the politics of powerful nations.

He didn’t want India to align with one group of powerful countries against another. At that time, there were two major groups: one led by Russia and the other by the United States and Britain. Nehru believed that India should be friendly to both but not formally join either side. He acknowledged that both America and Russia were very suspicious of each other and other countries, which made India’s path a tricky one. He also recognized that India might be seen as leaning toward one of these superpowers by both, but he thought this couldn’t be avoided.

Source: The New Indian Express

In a speech to the Constituent Assembly on March 8, 1948, Pt. Nehru clarified that non-alignment wasn’t merely a set of rules to follow but rather a method to be judged by its outcomes. He emphasized the importance of not relying too heavily on one side in international relations. From a practical standpoint, he believed that having an honest and independent foreign policy was the wisest choice, even if it seemed opportunistic.

In a letter to his close friend VK Krishna Menon in August, Nehru admitted that he no longer had much confidence in his ability to handle complex problems. Nonetheless, he found the behavior of the world’s Great Powers towards each other surprising. Regardless of the principles at play, he was struck by the sometimes-crude language and actions of these powerful nations in their interactions on the global stage.

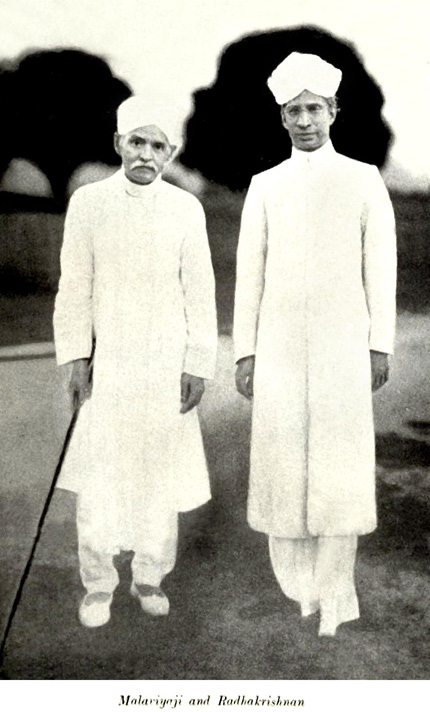

Between 1939 and 1948, Dr. S Radhakrishnan took on the role of Vice Chancellor at Banaras Hindu University. He did so at the urging of Mahamana Pt Madan Mohan Malaviya, who saw the need for strong leadership in this rapidly growing university. Dr. Radhakrishnan, a philosopher well-versed in both Western and Indian philosophies, oversaw the establishment of a technology college focusing on various branches of engineering. He also introduced graduate and post-graduate programs in law and social sciences and created a college of ayurveda. Much like Mahamana, he had unwavering faith in both modern sciences and ancient knowledge.

During his time at BHU, Dr. Radhakrishnan continued to support the freedom struggle and held great respect for Mahatma Gandhi. In January 1942, during the silver jubilee celebrations of BHU, Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. CV Raman visited the university. Their speeches and interactions from that event are still remembered today as a source of inspiration for those dedicated to fighting against colonial rule.

In 1949, Dr. S Radhakrishnan made a significant transition from the academic environment of Banaras Hindu University, situated in the timeless city of Kashi, known for its ghats and temples, to the forefront of global diplomacy. Prime Minister Nehru saw in Dr. Radhakrishnan a personality capable of representing and defining Indian values on the world stage.

During the period of 1948-49, relations between the Government of India and the Soviet Union had soured. One major reason, as highlighted in S Gopal’s biography, was the Soviet Union’s influence on the Indian Communist Party, pushing them towards rebellion and openly criticizing the policies of the Indian government. This diplomatic tension had significant implications for India’s foreign relations during that time.

Source: The Economic Times

Pt. Nehru was direct in expressing his desire for friendship and cooperation with Russia across various domains. However, he emphasized India’s sensitivity to criticism and disapproval. He criticized Russia’s policy, which he perceived as rooted in the mistaken belief that India had not fundamentally changed and was still a follower of British colonialism, a notion he deemed nonsensical and likely to lead to erroneous decisions.

In this context, Mrs. Vijayalakshmi Pandit’s role as the Indian Ambassador in Moscow was inconsequential, as she struggled to establish contacts and failed to secure an audience with Marshal JV Stalin. Rumors circulated that Stalin found her to be arrogant and aristocratic. Amid this unfavorable atmosphere, Dr. S Radhakrishnan assumed his role in Moscow, guided by Pt. Nehru’s counsel to proceed cautiously, avoid going too far, and closely monitor the reactions of the United States and Britain.

Dr. Radhakrishnan managed to break the ice with Marshal JV Stalin successfully. Top-secret telegrams from the Indian Embassy documented their discussions in 1950 and 1952. The 1950 telegram reported that during their meeting, both parties expressed a desire to strengthen bilateral relations, with Stalin seemingly approving of India’s policy of neutrality and commitment to avoiding cold war tactics and anti-Communist pacts, as reiterated by Pandit Nehru in Colombo.

Source: Quora

Stalin asked about India’s plans to help poor farmers, and the Indian Ambassador assured him that they were making changes. A historian named Vijay Singh thought this conversation was very important. The Ambassador talked with Stalin in a friendly way and thanked him for helping India with wheat last year. Stalin said it was their duty. They talked about India’s politics and said they wanted to make progress peacefully.

Stalin thought some rich people wouldn’t like that. India also talked about their foreign policy, saying they made choices based on what they believed was right, not because someone pressured them. They also asked if a group could check if bacteria weapons were used in Korea. Later on, a lot of people suffered and died in the Korean War. After this, Dr. Radhakrishnan came back to India and became Vice-President in 1952, holding the position until 1962.